Last summer I met a man. He surprised me, made me pause, knocked my socks off. I didn’t even know I wanted him until I met him, had no idea he even existed. If asked to sketch a profile of my dream man I’d never have set my expectations so high for fear of being disappointed.

Martin and I met online, but the night we met in person it was just for a drink after I’d had dinner with a girlfriend. It’s hard to tell from an online profile and some messaging if you’re going to like a person in real life. I need to know how the person smells, if he makes eye contact, if he has nice table manners. I was the one who pushed for the meeting, but because I didn’t want to give him too much of my time, I suggested we simply meet for a drink after my girl-date.

“I’m going to be more dressed up for our first date than I normally would be,” I warned him, and the disclaimer was unspoken but understood: I didn’t dress up for you.

I live in a place where people get judged more for dressing up and having nice things than for being casual, and it would be reasonable for a person to show up for a first date straight from floating the river. I wore a cotton dress, but instead of flip-flops I had on sassy high-heeled clogs. My hair was washed and not in a ponytail and I wore both jewelry and mascara. Instead of a sweatshirt around my waist I had a pretty shawl in my purse.

Martin arrived first and told me he was sitting in the back. He stood up when he spotted me, and when I arrived at the table we hugged, but honestly it was more like him holding me up. He wore well-fitting linen pants, a pressed shirt, and dress shoes. He wasn’t wearing his blazer at that point, but if he had I might’ve just hit the floor right then. It wasn’t just his looks. He oozed confidence and sincerity.

“I figured you’ve probably had your fill of guys in Carhartts and Chacos,” Martin said, “So I got a little dressed up for you.” It wasn’t just a one off. Still, even when we go out for Sunday night burgers he wears a blazer and good shoes.

The beginning was thrilling and filled with the jitters and nerves that accompany the excitement of a new relationship, but it didn’t take long for us to fall into a routine that felt comfortable and safe. Martin does all of the little things that added up to the big thing. The first time he brought me coffee in bed I thought it was a fluke, a kind gesture to make up for him getting out of bed at 6:00 on a Sunday to run eighteen miles, but no. Then I thought maybe it was a Sunday thing, or a weekend thing, but no.

Even on days that Martin doesn’t have to work he’ll set his alarm so he can make fresh coffee and bring it to me in bed. Even on days that I don’t have time to linger, he sets it on the nightstand so I have the luxury of starting my day with a few sips while I’m still cozy under the covers.

We spent our first ten or so Saturdays together at the farmers’ market. I’ve always been a fan of going early to beat the crowds, but Martin likes to go later, eat brunch there, and then shop. It only took me about a week to adapt. Going to market with Martin quickly became my favorite thing. I loved that he’d take my hand and hold it, kiss me just because, wait patiently while I chatted with endless numbers of people. I’ve always hated the question, “What’s for dinner?” but with Martin I liked it and I wasn’t afraid to tell him. In fact, I wasn’t afraid to tell him anything, and our relationship—even in the early days—had a marked absence of fear.

I have a fourteen-year-old dog, and warned Martin that dating a girl with an old dog can be tricky. For starters, Lucky comes first, which Martin reported was obvious from the start as Lucky had not only been in the car during our first date, but had also sniffed him out. More important is the reality Lucky will die sooner than not and I don’t know what will happen to me when he does.

“I could come unraveled,” I told Martin, “Completely undone.”

Martin held my face and looked me in the eye when he said, “He won’t leave until he knows you’re in good hands.”

My mother came to visit in September and Martin was incredible with her, but during that visit Lucky stopped eating, drinking, or walking for a couple of days. Martin showed me who he is in a crisis: clear, calm, and present. He’d baked my mother a cake for her birthday, but entered my house to find five of us hovering over the dog bed.

The cake he baked was a German recipe that translates into “gentleman’s cake,” which turned out to be perfect for Lucky’s funeral. Martin brought joy into the room where the air was heavy with heartbreak. It was a gorgeous late summer day, but we sat in the living room with the curtains drawn, the only light a thin column coming through the front door. It appeared we wanted to sit in the dark and wallow.

“Let’s take him outside,” Martin said, and we all looked at him like he was crazy. “He needs space,” my pragmatic guy continued, “and air. You’re all so crowded around him.” It was true. All of the fresh air in my house had been consumed by our sighing and heavy breathing. It was stale. It felt sick. It wasn’t helping. We carried Lucky out of the house on his dog bed.

“He’s like Aladdin,” I said, and he really did look like a little prince being carried into the sunshine on his magic carpet, his portal to the afterlife or maybe just to the yard. We let Lucky have some space in the last bits of light which turn quickly that time of year into alpenglow off the mountain across the street. In September this light is warm and pink, yet the air is cool.

It’s a decadent thing to have your dog bed in the front yard, and Lucky looked so peaceful, but eventually his body felt cold to the touch so we carried him back inside and into my bedroom. Everyone else went home, but Martin stayed with Lucky while my mother and I went to pick up slices of pizza; a whole pie seemed like more than we could manage.

Every breath seemed like Lucky’s last. The following days Martin did an extraordinary job bringing presence to Lucky’s downslide, while keeping us rooted in some of our normal activities. We went to the farmers’ market. We went to our friends’ house to pick plums. We hiked the mountain across the street—just the two of us, a first—while Luck’s grandma watched over him. Tears streamed down my cheeks all the way up the trail, and Martin rubbed my back and gave me kisses. It was nearly dark when we got to the top and nobody else was there. The sun dipped behind the mountains and my dam broke.

“I don’t know who I am if I’m not Lucky’s mom,” I wailed, “Who am I without someone to feed and walk?” One of the first things I noticed about Martin the night we met was his intense gaze; it’s unwavering. It made me nervous at first, but then I recognized it as a safe place.

“You will always be Lucky’s mom,” Martin said.

In the middle of the night I heard rustling from Lucky’s bed, little more than an arm’s distance from mine, so I ran to get a piece of bacon, the litmus test of life in a dog. He had no interest. I held the shallow dish of water under his chin, but he didn’t even seem to notice. Martin woke up, propped himself on one elbow and was patient while I sat and cried into my dog’s neck, which smells better than anything I’ve ever known. A quarter-sized piece of bacon sat perched on my knee.

I kept trying with the bacon, alternating between trying to get Lucky to recognize it as his favorite and wetting his lips with a paper towel soaked in water. Martin closed his eyes.

“He’s taking it! He’s taking the bacon!” I squealed. I ran to get more and then fed Lucky strip after strip of bacon. At exactly the same time—but I had no way of knowing—my father was having emergency heart surgery in North Carolina after suffering a heart attack.

The next day Lucky had almost completely reclaimed his groove, and my mother went home to New York. I had a visit planned later than week to see my father in North Carolina, but my flight was cancelled. Driving back home from the airport at 6:00 in the morning, Martin said that he thought Lucky had a hand in this, like maybe he knew his Mommy needed to stay home and rest.

It’s true. I was exhausted. It had been a long summer of running around and I need to be still. Martin set up his hammock with a sleeping bag and pillow so I could read and nap in the sun. He worked in the yard, then baked a cake with the plums we’d picked the previous weekend. He whipped fresh cream.

It had been a hot summer, so there hadn’t been any baking, but with cooler temperatures on the horizon and a few family crises I learned something about Martin: he’s a stress baker. He bakes everything from scratch. When things are falling apart he takes ingredients one at a time and carefully measures them, taking the bitter and making it sweet.

The first couple months of our relationship were filled with joy, yet there had been—for me—a low-grade, underlying grief: I wished I’d met Martin sooner. When my mother has a question she want to ask but is hesitant she prefaces it with another question, “Can I ask you a question,” she’ll ask. This annoys me sometimes and I’ll respond, “You just did,” but that doesn’t slow her down.

“Where has he been?” she asked as if I knew the answer, which I didn’t. The truth was, if Martin had showed up in my life five or seven years earlier there’s a good chance I wouldn’t have been ready for him. By the time he arrived I felt a bit overripe and perhaps ready to be made into a pudding or quick bread, but he quickly stopped the process and renewed my hope.

I hadn’t lost hope in a hopeless way, I’d simply removed expectation. After taking care of my grandmother with dementia I lived with more present-moment awareness than ever before; I was happy with the life I had as opposed to wanting something that might or might not be available to me. But then Martin appeared—a true vision in linen pants with an enormous heart and brilliant smile—and I felt grief. I’d finally met a man who I felt like I could have a family with, but I was forty two and he was forty seven.

The summer I was thirty I’d just broken up with a great guy and Lucky and I moved into an apartment by ourselves. Every morning we walked to a bakery for coffee and a croissant, and I taught him how to walk off leash because every few steps I’d give him a tiny bit of our pastry. I loved being a young mother to my pup. I got to know the owner of the bakery, and sometimes we’d chat. She told me that she never wanted children until she met her husband, and then suddenly it was all she wanted. I didn’t get it, but suddenly, twelve years later, her message was clear.

I talked about this fairly extensively with a few of my best girlfriends, but not to Martin. I know now that I can tell him anything, but I didn’t want him to think that I thought I was missing out. But really, I didn’t want him to run away. Talking about having a family—or lamenting the thought of not having one—was a premature conversation for us to have after two or three months. I wanted us to stay present; we were good there.

During this time my best friend Emily was pregnant. We’re exactly the same age and have embraced lives that were more adventurous and explorative than rooted and oriented toward family. If she could have a baby at forty-two then maybe I could too. We talked about it at length. And then some.

Emily’s baby was born in October. I’d been through an emotional ringer the past couple of months—my ex-husband died, Lucky almost died, my father had a heart attack—and I felt cut to the root and emotionally exposed. I was o raw and gutted over Lucky’s slow dance with death that I worried I didn’t even have the strength and stamina to be a parent. I reckoned I’m just too sensitive and emotional.

But I’d seen how Martin weathers a crisis or two and how much love and tenderness he extends with ease and grace. It made me want a family with him even more, so when Emily asked me—with her newborn in her arms—what I was thinking regarding making a family with Martin, I stood there in the shadow of the mountain and said, “I’m not thinking about it. I’ve stopped thinking about it. I’ve accepted that he and I—with Lucky and the dogs of our future—are enough.” She nodded the way she does, and we hugged and kissed goodbye.

Four days later I got something I wasn’t expecting: I got a positive pregnancy test.

I’d driven down to Jackson, Wyoming to visits a wonderful group of old friends, and was staying with my friend Sam, who’s like a sister. We were enjoying the afternoon sun on her deck, and I casually mentioned a few symptoms.

“Are you pregnant?” she asked, “Let’s go pee on a stick.” We giggled like kids en route to her bathroom where she sat me on the potty with a pregnancy test and told me to pee. She got in her bed, but with the door open we could still talk to each other.

“What does it say?” Sam asked before I’d even stopped peeing.

“Nothing yet,” I told her, then a few seconds later the air was sucked out of me. “I don’t know,” I said, “I feel like it’s dark in here and I can’t really see. I feel like I’m wearing polarized lenses and I’m seeing lines that aren’t really there. I’m not sure.” I touched my face just in case, but my sunglasses were nowhere to be found.” Sam came into the bathroom and took the stick out of my hand.

“This is a positive pregnancy test!” she squealed, “Oh my god. You’re pregnant!”

Not sure what to do, we climbed into her bed with our dogs, a scenario we’ve spent countless hours in over the past fifteen years that we’ve been friends. We do our best thinking in beds with dogs.

I had plans to go meet two other friends, and knew I couldn’t keep my exciting news from them, but I knew that the next person to hear this news was going to have to be Martin. I took a shower, and as I drove across town I called him. I had a hunch he was going to be delighted, but I was wrong.

“How did this happen?” he asked, and I had no answer, but reminded him that he’s forty-seven-years old and I didn’t think he needed a biology lesson. There was a lot of silence from his end. I asked him if he was still there.

“I had to sit down,” he said.

It was awkward. I couldn’t see him, feel him, or smell him. I wanted to reach out to him, but I was four hundred miles from home. I apologized for having to tell him this way, but I told him I couldn’t wait. He was glad I told him, but I felt doom from the other end of the line. The only thing Martin said during that conversation that gave me any confidence was, “Everything will be okay.”

I was fortunate to be seeing four of my dearest girlfriends that weekend and to be able to share shrieks of joy with them, which made up for Martin’s lack of enthusiasm. I held my friend Danielle’s miracle baby as I told her, I walked in the twilight at the Elk Refuge with my college friend Julia as I told her. There was so much joy.

Julia worked some magic and got me an appointment with her astrologer friend for the next morning. I sat with Lyn and told her that I couldn’t quite believe it, but I felt the presence in my abdomen. She told me she saw two babies in my chart, and I panicked over the thought of twins.

“Is is possible that one of the babies is a book?” I asked her, “I’m writing a book, and, well, now I suddenly have the deadline of all deadlines. It would be helpful if one of those babies is a book.”

“It’s quite likely,” she said with a smile. Lyn and I talked about Martin. As with everyone else, when asked about Martin’s reaction I described our conversation and said it was a little iffy. Lyn and I talked about the strong mothering presence in my chart and how I could do this alone if I needed to. I told her I had no doubt about that, but I was also honest with myself and with her as my witness.

“I want a family,” I told her, “My family has been me and Luckydog for years, and I could see myself being a single mom—having that family would be far more than enough—but that’s not exactly how I pictured it.”

The next day I drove home. The drive home was so different than the drive down just three days earlier. I started my drive fresh out of a soul-affirming brunch and walk with Mariah, who I met the summer after I returned from my year in Honduras, the summer after she graduated from college. Mariah and I were in different places then as we are now, and as we always will be—there are eleven years between us—but our hearts are aligned in a way that transcends time. I started home with sore cheeks from so much smiling.

The first couple hours of the drive were a breeze. The sun was shining and I listened to the recording of my reading with Lyn. I knew it would mean finishing the drive in the dark, but I stopped at the Patagonia outlet anyway. I wanted to buy myself some long underwear, and I didn’t go in looking to buy anything for my four-week-old embryo, but I couldn’t resist the little down jacket and fleece vest that would fit him his first fall and winter. I know now that this was not a wise decision.

I got back on the highway headed north, and had the unfortunate happenstance of stopping for gas right as the last light was fading. When I got back into the car it was pitch black. Hunting season was in full swing and I kept my eyes peeled for animals crossing the road, but also for pickups with big game in the bed. I knew it was likely many of these drivers had been drinking. Beer and hunting—especially when the hunt fills a tag—is a natural pairing in Montana. One driver rode the center line for miles, and when he finally edged to the right I drove faster than I usually do in the dark, but it felt safer than staying behind him. I pushed my odometer to ninety—knowing that’s nuts at night—but I begged a cop to pull me over.

If I got stopped I knew the first words out of my mouth would be, “Where have you been?”

It felt different out there on the interstate knowing I was pregnant. I felt like I needed to be more careful, but I also felt desperate to get home. I drove the last eighty miles clutching the wheel both because of what was going on around me, but more because of what was going on within me. I had a lot of practice conversations in my head.

When Martin and I made the decision to have less-safe sex I presented him with a bullet-point list of facts. I’d never stated it quite like this before, but perhaps my intuition had a suspicion something might be at stake. The most important thing I told Martin was that if I got pregnant I would have the baby. I also told him that I would always let him know where I was in my cycle, and that I would share the contraception responsibility but not take it on as my sole responsibility. I was clear that I wouldn’t consider an abortion, but I’d consider taking Plan B if we thought it was necessary. I also told him that if he thought that having a baby with me would be life ruining and the worst thing to happen to him that he should never even consider unprotected sex because a woman’s cycle can be fickle, especially at my age.

Based on this succinct conversation I figured that while Martin might’ve been surprised by the news of our pregnancy to the point of needing a seat, he’d accept responsibility and be happy about the family we’d create. But on that dark drive to his house I also prepared myself to let him go. I wanted to be clear that this was something I really wanted, and if he didn’t I would understand. I wept as I said the words aloud to myself in the car.

“You don’t have to do this if you don’t want to,” I practiced, “I understand, and I don’t want you to force yourself to do something you don’t want to do. Worse than not having a family with you would be you doing it out of obligation, so please don’t do that.” I made myself cry.

“I will tell our child about when we met,” I continued, despite the fact that adding tears to this already dicey driving situation was probably not wise, “I’ll tell him about what a kind, smart, beautiful man you are and how wonderful you are, but that you just didn’t want to be a father.” I was sick to my stomach by the time I arrived.

When I turned the corner to his house I saw Martin in the kitchen, and when I opened the door the first sensation that hit me was the evidence of baking, the warmth of cinnamon. If I knew nothing else to be true I knew this: nobody bakes a breakup cake. Lucky ran toward the kitchen while I took off my boots.

“Hey, stinker,” Martin said, “Welcome home!” I heard joy. I felt love. I was home.

Martin greeted me with a soft, gentle smile and a strong hug. I cried into his chest, and for awhile neither of us spoke.

“I talked to Marietta,” he said finally, “And Thanksgiving dinner will be at 2:00.” He wasn’t dumping me. That was all—in that moment—that I needed to know. We went out for burgers, and then home to eat his apple cake and get to sleep early. We were exhausted.

That whole evening we didn’t even talk about the pregnancy. At first this concerned me, but then I realized that the most important thing was that we connected to each other. We held hands, looked deeply into each others eyes, and fell asleep cuddling, but in the morning I was anxious. As we ate breakfast I told Martin that I was glad we took that time to just be together, but that we needed to actually talk about the pregnancy. He agreed, but the next time we both had available was Thursday evening, otherwise known as an agonizingly long time away from Monday morning.

In the meantime I got to see Emily and baby Nina, I hosted some of my dearest friends for a birthday dinner, I met friends for hikes and tea. I got to tell a lot of people my exciting news. The news of my pregnancy was just a week after the election, and I got to be the bearer of good news in a world that had, overnight, turned more complicated and confusing than ever. I got to feel a lot of joy that week with many of my closest friends, but I still wasn’t sure how my boyfriend felt about all of it.

I was already pregnant the week before I found out, and I put on a pair of jeans before heading over to Martin’s. He put his hands on my waist to pull me in for a hug, and I said, “Ick, my jeans are tight today.” Martin kept his grip on my waist and looked at my belly before looking at me and asking, “Are you pregnant?”

“No!” I laughed, but the sweet way he asked the question made me believe he wouldn’t think pregnancy wouldn’t be the worst thing to happen to us.

Thursday came around and I made a beef stew to bring over and Martin picked up fresh bread. We chatted about the week as we ate, but the longer it took to talk about the baby the more my anxiety grew. Finally we settled in on the couch. I curled myself around him and prepared for the worst. I’d yet to see joy from him regarding the pregnancy and I wasn’t expecting it. I asked him how he felt.

“Concerned,” he said, and I peeled my body away from his a little bit. “I’m concerned because of our ages, because of all that can go wrong with a pregnancy. I’ll be close to retirement when the child graduates from college, my parents are getting older and it’s harder for them to travel. This will mean more trips to Germany. I worry about what having a baby will do to our relationship, what losing a child would do to our relationship.” He also talked a little about the upsides, that we’re more financially and emotionally stable than many people in their twenties and even thirties who are having babies, but the scales were far from even.

“I worry about our energy,” he continued, “Do we have the energy for a child? What about a child with special needs?” He told me that ten years prior if he thought he wouldn’t have a chance to be a dad he’d have thought he was missing out, but as he grew older he let go of that. I laughed and told him that ten years earlier if I’d had a baby I’d have thought I was missing out. We were coming at this thing from completely different points of view.

Martin’s points were valid and I told him so, but I also told him that I was optimistic. I told him that statistics are complicated and we’re both healthy. He told me that paternal age is more of a factor on a baby’s health than I might realize; he’d been doing research.

When he asked me how I felt I answered, “Excited.” I struggled to see this guy, whose heart is light, force a smile. I fell back into the headspace I was in on the drive home from Jackson, and I told Martin that he didn’t have to do this with me, but I was going to do it.

“You don’t have to do this,” I said, “You don’t have to make a family with me. You can’t want something you don’t want.”

“I want you,” he assured me.

The next four weeks were a challenge. I was tired and Martin wanted his girlfriend back. Things that hadn’t been a question before were suddenly looming large. The major upside was that the most pressing question of all had vanished. I’d been pondering for years how I’d survive the death of Lucky—even in Martin’s good hands—and what I would do with myself on a day-to-day basis. The answer had eluded me, but suddenly it was clear.

“I’m going to take care of my baby,” I realized, “When Lucky dies I will take care of my baby, and if the baby hasn’t arrived yet I will take good care of myself.” I no longer had to worry if I’d sell everything and run off to Bali or if my sadness would wither me away to nothing. Just like Lucky had a hand in delaying my trip to North Carolina, I started to believe he had a hand in bringing me an against-the-odds baby.

Those of us who witnessed Lucky’s near death in September knew he was close. His eyes were vacant, his breath labored, his body lifeless. For a few hours that Saturday afternoon we gathered in Emily and Jeff’s yard as Martin picked plums, and over the course of a few hours we all felt Lucky slipping away. He might even have crossed over briefly before returning to us. Lucky is an old dog. He’s almost fifteen now, and it’s not like he’s going to live forever, we just get to enjoy him a little longer.

What I enjoy the most about Lucky—and the list is long—is not his cheerful demeanor, not his unwavering love, not even the smell of his neck. It’s his wisdom. He is truly the smartest person I’ve ever known, and he only became brighter after his near-death experience. It didn’t take long to convince me that the only way I’d conceived a baby at age forty two while trying not to get pregnant was if Luckydog had a paw in making this happen.

It made sense. Perhaps Lucky thought I was prepared to let him go. Martin was the guy we didn’t even dare dream of, and he liked us too. Perhaps Luck had thought I was in good shape, and he had every reason to believe. That day in Emily’s yard we all got down close and talked to him. We told him he’s been such a good boy and that we love him very much. We said everything we could think of to let him know that he didn’t have to hold on if he didn’t want to, that he could let go if he was ready.

Martin crouched behind me and spoke to Lucky. He said, “You’ve taken such good care of your momma, Luck, but you don’t have to worry anymore. I can take care of her now.” Martin and Jeff wrapped Lucky in a blanket and placed him in my car, all of us certain we were taking him home to die. But he didn’t; he wasn’t ready.

I was eight weeks pregnant when I went for my first ultrasound. I’d been so worried that the images might show two babies, that I’d completely forgotten to worry about the absence of one.

Before the ultrasound I had a thorough exam and answered a lot of questions. I had many symptoms of a healthy pregnancy, and no reason to think anything was wrong. It was a transvaginal ultrasound, which means a probe is placed inside the vagina. Right before the midwife stuck it inside me she asked me why Martin hadn’t joined me for the appointment. It felt like an accusation, but I gave her the only answer there was.

“I didn’t ask him to,” I told her. I knew if I’d asked Martin he would have joined me, and I’d even booked the first morning appointment to make it easier for him with his job. But I didn’t ask him. In part I didn’t ask him because I knew it would be a long appointment that dealt with a lot of my health history and I didn’t want to waste his time, but I know now that I was afraid of the outcome.

Emily had asked me the day before if Martin was joining me and I’d told her no, for the same reason, and she pointed out that hearing the baby’s heartbeat is a great way for a father to connect with the baby. The mother is automatically linked physically, but the father just has a tired, cranky, swollen mother and that doesn’t always lead to feeling connected.

Of course she was right. But what happens when there is no heartbeat? What happens when the midwife turns the screen away from you to get a closer look and then turns it toward you, and with the cold probe still in your vagina, shows you the emptiness in your womb. She pointed out the size of the gestational sac and the slight fetal pole—the egg had implanted—but told me the baby had stopped growing after five or six weeks and that the pregnancy was most likely not viable.

When I heard that the egg had detached, the big question of what I’m going to do when Lucky dies came rushing back at me larger, louder, angrier than before. It was a slap. It had bite, now, when previously it only had bark. The option of having a baby to take care of had been removed from the menu, and now there was just me. I could just take care of myself, if I could.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t believe it. I was in denial. Grief can be like a moving target, but I refused to buckle under the weightiness of this unexpected plot twist within an unexpected plot twist.

I consulted other health professionals, some of whom are close friends, and I read everything on the internet. In some cases the ultrasound is wrong, and I held onto that hope. There had been a distinct shift to my nighttime fieldwork; I transitioned from staying up late researching non-toxic cribs to staying up late at night asking Google for how long will I bleed? I tried to be both realistic and optimistic, but until my water broke I didn’t fully believe I was going to lose the baby.

For nine days I waited to miscarry, which I now know is like waiting to exhale. I never considered a D&C, but I did consider taking a drug called misoprostal to encourage labor. I wanted the miscarriage to happy naturally if it was going to, and taking misoprostal felt like giving myself an abortion. I couldn’t personally do that without being 100% sure. I still felt as pregnant as I had before the ultrasound showed my blighted ovum. I felt I could breastfeed on the spot, and in many ways felt like my body had betrayed me. Purgatory is a lonely place.

I got another ultrasound that confirmed the first, and hoped it would help my body let go but it didn’t. I went to my writing group wearing a nighttime pad just in case, and despite my red-rimmed eyes and hollowed out heart I participated in the conversation as if nothing was wrong. I went to work. I told a few of my coworkers who I share shifts with what was going on because I wanted them to know in case I started cramping during a massage and had to leave in a hurry. One of my coworkers had a miscarriage and when I told her the waiting was the hardest part she said, “No, the worst is yet to come.”

It was the most honest thing anyone had said to me regarding the miscarriage process.

“If it happens at work you won’t be able to drive home,” she said, and that was actually the closest I got to comprehending that a miscarriage is far more than heavy bleeding and bad period cramps. Women don’t like to talk about their miscarriages, about how their body failed at the one big job it was designed to do. Some bodies fail at the simpler tasks, the ones we take as a given—breathing, digestion, happiness—and when those systems fail us we don’t do much like to talk about them either.

By day seven my patience had worn thin. A dear friend was having a double mastectomy the following day, but she stopped by in the morning to bring me chocolate because we know that chocolate always helps. She was also the first person to bring me a congratulatory gift—tea, chocolate, prenatal vitamins, and a note telling me I was going to rock it. Neither of us wanted to believe we were in danger, but we worried about each other.

At a birthday party we laughed—even though it wasn’t funny—and agreed that I could worry about her and she could worry about me but we wouldn’t worry about ourselves. It seemed easier, I guess, to keep that distance from our own potential pain. That night at that party neither of us knew how complicated our situations were going to become over the next few weeks. She only needed a single lumpectomy, I was having a healthy first trimester. Boobs seemed to be our only problem.

Three weeks later things had changed dramatically for both of us, we could hardly keep up with the emotion and it felt easier to be strong. We stood there in my living room and cried, though neither of us really let go. We were both scared, yet at the same time fearless. The list of unknowns lengthened by the minute, and questions we didn’t even know we had multiplied until even our questions had questions. It was hard to determine which ones needed answering and which ones would remain mysteries. Neither of us drowned, but we swam hard.

I went to work that day, but not the next. Day eight was spent preparing. I saw my Osteopath and my Naturopath for care and supportive therapies. I changed sheets and cleaned the house. I stocked the fridge. I’d bought all the right stuff: apples, almond milk, letting go bath salts. I put together baskets of items I’d need—one with dark towels, one with cozy pants and tops, one with undies— so I’d have easy access to it all. I’d bought pads and wipes and set those in the bathroom in another basket. I mothered the shit out of myself.

I’d made a soft decision earlier in the week that if the miscarriage hadn’t happened naturally by Friday that I would take the pill so I could recover over the weekend. I laugh now—a month later and still recovering—that getting back to work on Monday was a priority. Blake gave me advice I wish I’d had the wisdom to heed, “Protect yourself. Don’t push pain.”

My body finally cooperated. For nine days my body had fought an inevitable process as it refused to let go of an embryo that had stopped developing three or four weeks prior. Martin came over. I was in the bathtub when he arrived, and he sat on the little stool and rubbed my head while I wept. I wept because of the agony of waiting, because of my fear of the pain, because of the outcome that I wasn’t sure I could accept. I was in it. This was not a story I could step out of.

I was weary and weak, and after soaking for well over an hour I asked Martin to dry me off, and he did. I put on underpants and a pad and he tucked me into bed. I don’t know how long Martin sat on the edge of the bed, but it was long enough that I was drifting off to sleep. I told him I had slight cramps, but nothing too bad. He left and we said we’d talk in the morning.

I was crampy during the night and aware of it, but I slept. About an hour before the sunrise I got out of bd and started moving about the house without thinking. I turned up the heat. I put on the kettle for tea. I ran water for a bath. I moved with purpose, yet it felt like a walking meditation, like maybe half of me existed on another plane.

I added salt to my bathwater and set my tea on the ledge of the tub. I was cold and ready to submerge myself. My water broke as I slipped out of my pants. I felt it burst and heard it hit the bathroom linoleum. It seemed louder than it was supposed to be, and at first I didn’t even know what it was.

I wasn’t expecting my water to break. I was only nine weeks pregnant, and despite all of my reading on the internet I didn’t have a grip on what was actually going to happen during the miscarriage. This is in part because every miscarriage is different, but also because I’d mostly been reading the stories about the cases where the ultrasound was wrong and the woman went back at ten weeks and the heartbeat was strong.

The other part is that a lot of women don’t want to talk about it, not to their friends, not to strangers on the internet. It’s an incredibly emotional thing to go through, and difficult to process on the fly. Then, when these mothers have recovered, they just want to move on and don’t necessarily want to relive the experience.

I wiped up the floor and got into the bathtub. I texted Martin, Emily, and Charlotte. They all offered to come over to provide support, but I told them it was an inside job.

The contractions took me by surprise. I hear from people who’ve experienced both miscarriage and live birth that the contractions during a miscarriage are almost worse. I think that’s in part because of the body’s physical experience of grief and knowing that in the end there’s not going to be a baby, but rather a void. I think the other part is purely physical, sort of how it’s almost more painful to dry heave than it is to vomit. During a miscarriage the cervix is dilating and the uterus is contracting to remove the tissue, placenta and sac, but there’s so little in there it aches against the pressure of itself.

As the contractions increased I quickly changed my mind. I was screaming and writhing in the bathtub and I had no idea how long I’d be there, but wanted to make sure Lucky was taken care of so I asked Martin to come walk him. It had snowed overnight, but was hovering just above zero that morning. Martin told me he’d clear the car and be over.

I discovered pain that has edges. It didn’t appear to have limits.

I put on classical music and tried to remember to breathe. At some point I texted Martin, “Please come straight into me.” I was worried he’d walk Lucky right away, which was silly, and I’d be left freezing in the bathtub, which I’d since drained. I was sad the night before when he found me crying as I soaked, but this was a whole new level. I was full-on primal, squatting in the bathtub, streaming blood and rinsing it away with water from a plastic cup. I was so cold.

“Get me out of here,” I pleaded when he opened the bathroom door.” I had a contraction then and fell back in the tub. “This is so much harder than I thought,” I confessed, “I had no idea.”

I repeated that line a lot over the next days—I had no idea—and still, as I continue through this process, I have no idea.

Martin got me into bed as the contractions continued. The pain was close to unbearable. The morning classics played and were calming, but the music sounded both near and far, a perfect metaphor for my experience. Martin gently stroked my face and brushed my hair off my forehead. The contractions got closer and the intensity continued to build. I hadn’t expected labor or delivery. There are a dozen “What to Expect” books for pregnancy through the preschool years, but nobody thought to write a book—or even a measly pamphlet—on what to expect when you lose your baby.

Exhaustion took over and I closed my eyes. I fell asleep for a few minutes, but I was aware of Martin’s presence, his weight on the edge of the bed like an anchor holding me in place. When I woke up and opened my eyes I asked Martin how much time had passed, and he told me it had been about thirty minutes.

We asked each other, “Is it over?”

It was. In many ways it was over, but a hundred times more ways it was just the beginning.

I texted my friends, and told them, “Emotionally I feel calm, clear, and aware. I love this aftermath of a trauma: even though it was difficult, stretching, exhausting, devastating…I still wouldn’t trade the experience and know I’m better for having had it.”

Charlotte, who in addition to being a friend who guided me through this, is a midwife, and she commended me for trusting myself to allow the process to happen naturally and for trusting my inner wisdom. She recognized the empowerment in relinquishing control over the inevitable, and tapping into my own insight and groundedness to find my reserve tanks of strength.

She said, “Seeing a best friend be so in charge and in control and trusting and working with things like this.. such a mysterious process…is pretty much the central love of my career. I work everyday and have for years for patients to have this sort of experience, so to witness my friend being so in tune, just sends me to the Stars, although it has been a very hard and perplexing couple of weeks. It makes me know that I am doing the right thing, in my cells to see you be so Amazing.”

My mother said, “I’m always so proud of you.”

Most people don’t share their pregnancies in the first trimester, and even though I felt like I didn’t tell everyone—just my local friends, people at work, a few old friends across the country, people I saw and told because I couldn’t contain my sweet secret—the numbers added up. I sent several dozen texts to relay the sad news.

It was crushing to have my friends’ hearts break along with mine, but I was glad for the support, which would’ve been harder to ask for had I not told people I was pregnant in the first place. So many people suffer silently—with miscarriage as well as with illness, heartache, etc.—and that only leads to a deeper struggle, to more suffering, to more disconnection from ourselves and the world. Breaking open is difficult, but it’s worth it.

Friends delivered candles, flowers, soup, chocolates, essential oils, books, sexy tank tops and cozy leg warmers. I sobbed over a goody bag with a mug, my favorite teas, a candle then when lit looked like a little sun, and an apology note from a friend who hadn’t intended to hurt my feelings. I drank fresh juice, herbal teas, and broth. Friends told me stories of their own miscarriages, and how they grieved and healed and built strength. I felt guilty for not knowing how to support them when they went through it, for not having the empathy to understand the depth of the loss.

My dear friend Julia—who hooted and hollered with me under the rising moon in Wyoming when we were celebrating—offered to drive half a day over the snowy mountain passes to support me. I knew that all I had to do was reach out and a hand would be there, but for the most part my friends knew that what I needed was space to grieve and the security in knowing I only had to answer the question, “What do you need?”

A lot of my grief was silent. I didn’t take much time to recover and I went back to work, to the gym, to making dates for lunches and hikes. It was too much. I was physically, emotionally, and hormonally depleted. I continued to downplay the emotional and physical trauma of a miscarriage until it played me down.

Most of Christmas weekend I sobbed. Martin, Lucky, and I hiked through deep snow to cut down a tree, and when I stopped to pee I saw my blood in the snow and it unhinged me. Martin asked if I was tired, and I was. I told him yes, but I as far as I could. I didn’t trudge through the even deeper snow to the place where he found our perfect tree, but I stood and listened to the rhythmic saw, soaked in the pine smell which invigorated the air.

By the time we got home I’d whipped through my already low reserve tank and had nothing left to even help him decorate the tree. I drank tea and snuggled on the couch with Lucky and watched Martin wrap lights and hang ornaments. I cried over my lack of involvement, and he gave me a simple job of tying silver string on cookies so I could participate in our first Christmas together. Martin never faltered, and has cared for me throughout this ordeal in a way that is nothing less than extraordinary.

The next night we drove through a blizzard to have dinner with his family up the Blackfoot, just past my favorite beach, where we’ll go when it thaws and have a ceremony. We went to church and sang Silent Night with candles in our hands, and he rubbed my back when I cried not because it was sad but because it was so beautiful.

Emily and I talked about how loss is sort of a homecoming, how enduring a great loss can be the path that leads us home. I thought Lucky had this miracle baby sent to me to pick up where he leaves off, but I was wrong. The baby came to show me intense loss, Lucky stayed to show me how to endure it.

This miscarriage has left me emotionally strong but physically weak, and I’ve had to accept that. I did too much, too soon, and I learned a lot of lessons about how to heal. I pride myself on my strength—both inner and outer—and confessed to my Osteopath that I’d been hiking and lifting weights at the gym, but that it wasn’t working. I told him I wanted to go running because that’s been how I’ve regulated my emotions since middle school, and it was driving me crazy that I don’t have the energy. I wanted to feel strong by building strength, and I didn’t realize that in order to feel strong I was going to have to submit.

“I don’t feel energized,” I told Matt, “I’m just so exhausted.”

He laughed. “Energized isn’t the goal. Calm is the goal.”

Matt told me to just be tired, and wrote me a prescription for rest. He told me to stay home until 1:30 for four days in a row, drink tea and broth, and watch and read lighthearted movies and books. I texted Emily a photo of my prescription, and a question.

“What’s a funny book?” I asked her because for the life of me I couldn’t come up with one measly idea. She rattled off a list and offered a delivery. It was frigid cold, and I didn’t want Emily and the baby running errands for me. Not only did she insist, but she also knew just the book.

When Emily and I celebrated our fortieth birthdays together in Portugal we were both grieving. I’d brought a funny book on the trip that I finished before we met, but it was worth lugging across Spain to watch her giggle as she read it.

That book (Where’d You go, Bernadette?) was on our bedside table the night we heard a sound like someone breaking into our apartment. I was fast asleep when Emily grabbed my hand in the middle of the night and told me she was scared. I held her hand and we were quiet as we waited for the noise to return. When it did I listened closely and took a deep breath after determining it had come from the apartment next door. The doors on the ancient buildings were five inches thick and swollen from the salty air; our neighbors were trying to close their door, not open ours.

“That’s the sound of a door closing,” I told her, and in that moment we both put a lot of our grief behind us. The book Emily bought for me is from the same author who wrote the book that made us laugh as we turned the pages on a new decade, and this one has a title that couldn’t be more perfect: Today Will Be Different.

Maybe we need to stop encouraging people to keep their chins up, and instead give them books, leg warmers and permission to sit with their grief. At the end of my line, I submitted to the deep grief. My vitality and fire are returning.

With my renewed clarity and a little distance I’ve realized that I didn’t just have a miscarriage; four weeks later I’m still having it. When I sat down to write this essay my intention was to write a lot more about the miscarriage process itself, but I realized once I began that what I needed to write was everything that led up to it. The essay about the miscarriage will come when its ready, when I’ve completed the full circle. When that will be is still a mystery, and I’m okay with that.

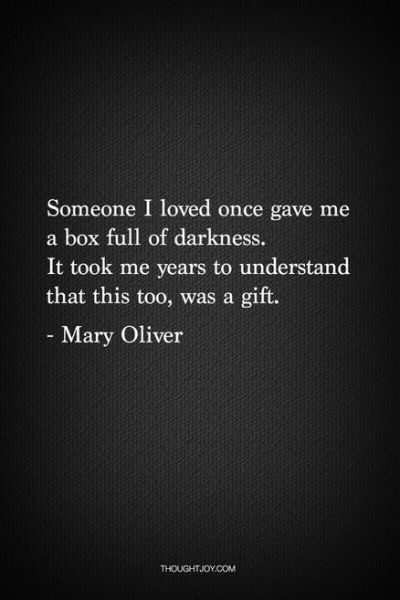

There were dozens of photos and quotes I wanted to include with this post, but I decided to let the words speak for themselves. Except this one.

I took this Wednesday driving up to Hot Springs, where I go to rest and restore, and where I also hoped to locate the strength to write this post. It worked. The catharsis from writing this essay has been tranformative.

After I posted the above photo to Instagram, my dear Emily commented, “…driving to the core.”

Yes, that’s what I did. I drove right to core. I drove it home. I drove myself straight to love.