Mimi often woke up in the morning disoriented, and began the day asking questions for which neither of us had the right answer. “Where’s Poppy” she’d want to know, and we’d tell her that her husband had died two year prior. “Jesus Christ,” Mimi said, “You’ve gotta be kidding me. Where the hell have I been?”

“Want more coffee, Mimi?” I asked, attempting to keep her in the present.

“How about Alice?” Mimi asked, “Alice hasn’t been around in ages. Is she mad at me?” Every morning while we nibbled on toast and scrambled eggs or Mimi’s favorite—a hard roll from the bagel shop with butter and jelly on both sides—Mimi inquired on the whereabouts of her husband and three sisters, and my mother and I took turns telling her—as if for the first time—that they’d all died.

By the time we reached the end of the line of questions, we’d barely get a breath in edgewise before Mimi started in again at the top. My mother often ran from the room, face in her hands either from laughter or tears, leaving me to break the news, again. Mimi wanted all the details for each person including cause of death, date of death, if Mimi had been notified, and if had there been a proper wake and burial.

“I can’t believe nobody told me,” Mimi pondered with each one, both hurt and pissed, her heart breaking dozens of times every day. In the beginning, my mother and I were patient, and we’d give her the details, but after multiple rounds we lost our stamina for the specifics, and answered Mimi’s questions with one-word answers:

Dead. Dead. Dead. Dead

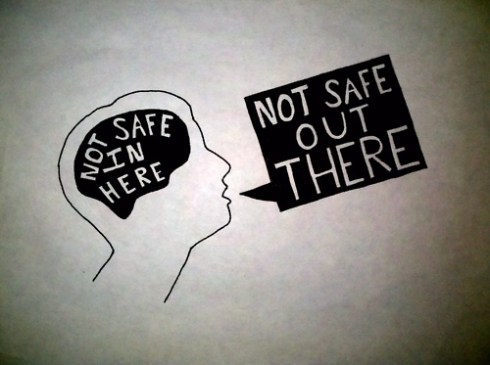

It was brutal and direct, but we were doing our best. We hated lying to Mimi, but my mother and I later learned that it’s best not to give more information than the dementia patient can process. For example, if they think their sister is alive but they just haven’t seen her lately, it’s best to keep it simple and respond with something neutral like, “Hmmm. You know, I haven’t seen Virginia in a little while either.” The middle stages of memory loss are tricky—Mimi couldn’t put her finger on it, but she had a hunch that she didn’t know. “I’m all mixed up,” she’d say to us, “I don’t know if I’m coming or going.” And then she’d laugh, because laughter was Mimi’s best defense.

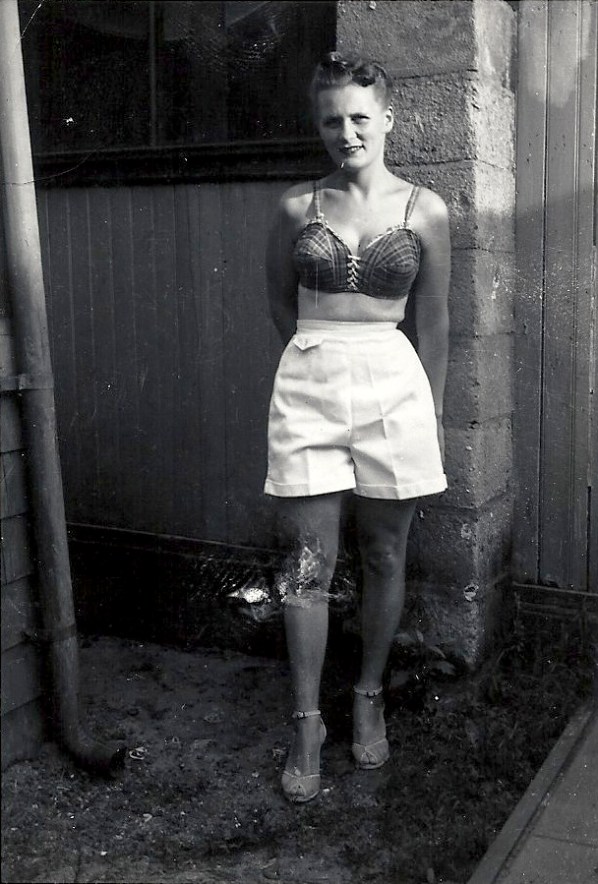

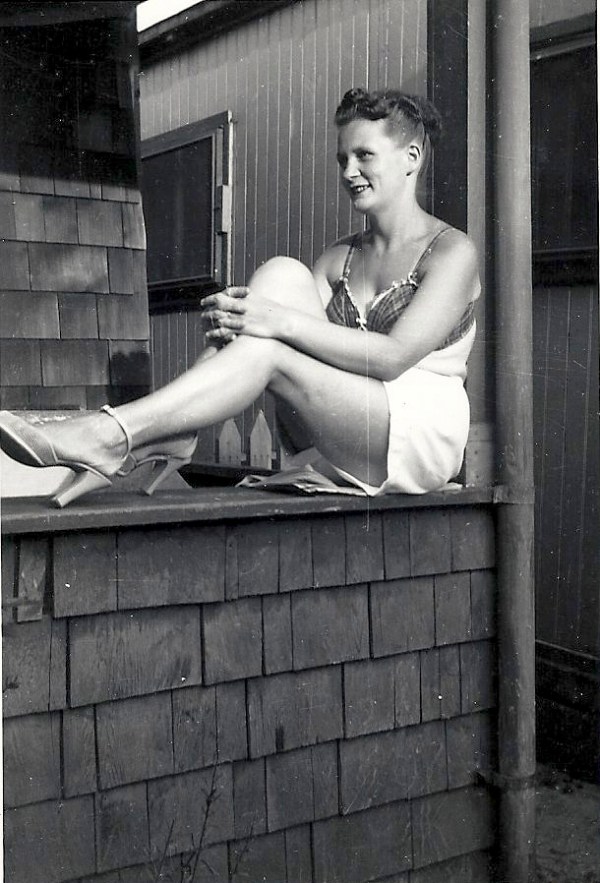

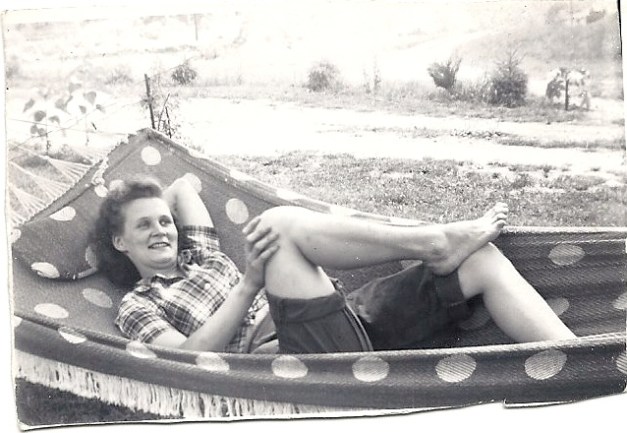

Mimi’s three sisters were her best friends and she saw them every day unless someone was traveling. They ate more meals together than they did with their own husbands, and it was as if Mimi could feel it in her body that she hadn’t seen her sisters. Lying to Mimi felt wrong, even if it was best for her, and when my endurance for the dance had worn out, I’d answer her question with another question. “How about lasagna tonight? We’ll make it from scratch, you and me?”

Shortly after I showed up to help take care of Mimi, it became clear to me that her mood was most manageable when we rooted in the present. We went for rides in the car, got manicures, and watched the news, but nothing grounded Mimi more than watching me cook. As the days turned wintery, we went for fewer walks and rides in the car, which meant more time in the house, which could be a danger zone for the three of us. “I can’t stay cooped up like this,” Mimi would say, “I feel like I’m suffocating.”

I came up with the idea to prepare our main meal of the day cooking-show style, which meant I cut and measured everything into little glass bowls before starting the performance. I did this so that the putting together of a meal leaned away from the utilitarian and into the territory of an actual event, though Mimi was the sole attendee to my show. I usually started right after breakfast, afraid that if we missed a beat Mimi might wander into dangerous mental territory, might get upset, might forget that she loved me. Left alone in the sketchy neighborhood that her mind had become, Mimi could get nasty. She’d get up in my face.“Who the hell died and made you boss?” My mother was always afraid Mimi would throw a game-changing punch. “Cover your teeth,” my mother whispered, covering her own mouth with an open palm behind Mimi’s back, as if me losing a tooth to my grandmother’s unlikely punch was our biggest worry.

“You have something to say to me, Maureen, you can say it to my face,” Mimi roared as my mother shrunk into herself even deeper. My mother was afraid of her mother—she was afraid to challenge her, afraid to confront her, afraid to lay down any sort of law. By default, it was up to me.

I tried to stay ahead of Mimi’s temper, like doctors advise staying ahead of the pain after surgery, so as soon as breakfast was over, I’d sit Mimi down at the kitchen table with a cup of tea and a cardigan draped over her shoulders. I peeled carrots, diced onion, and minced garlic. I filled little bowls with ingredients. I braised bones, caramelized vegetables, and reduced stocks into glazes. I deveined and reconstituted. I did not cut any corners. While I worked, Mimi and I chatted. We talked about what I was making, and I told her step-by-step how I was going to do it. I’d tell her about a childhood friend I visited, or a book I was reading, or a movie I’d watched the night before after she’d fallen asleep. As long as Mimi engaged in real-time conversation she stayed safe from the questions she couldn’t remember the answers to. I’d ask if she wanted to help, but she usually didn’t.

“I’m enjoying myself just watching you,” Mimi said, “It’s like being in the kitchen with Nanny, with my mother.” I loved that she loved it, so day after day I hunted down time-consuming recipes from The New York Times, Zuni Café, Marcella Hazan, Julia Child. I felt like a disciple to advanced cooking techniques, and sometimes worked on two or three meals at once, sweating the eggplant for the next day, brining the chicken for the day after that.

The downstairs kitchen, Mimi’s domain, remained like a warzone, but I filled our upstairs kitchen with smells of a home and loaded our plates with colorful, nutritious food. After dinner, my mother did the dishes while I sorted the leftovers, and Mimi stayed at the table. Sometimes, even after hours of being in the kitchen together, Mimi not only forgot that had I spent the afternoon cooking, but also that she’d just eaten a full meal.

“I don’t know what you’re doing babydoll, but if you’re fixing something to eat don’t worry about me. I’m not hungry.” Her words took out my knees. I slumped against the sink. I didn’t want to get mad at Mimi, didn’t want to use a sharp tone. I didn’t want to say, “Of course you’re not hungry! You just ate a roast chicken dinner and still have chocolate frosting on your mouth from the cake I walked twenty blocks to buy!”

My cooking-show pace wasn’t sustainable on a daily basis, and sometimes I was too emotionally drained to even think about cooking, so we’d eat leftovers or get takeout from one of the thirty ethnic restaurants in the neighborhood. There were also days that we had other responsibilities, like getting Mimi to a doctor’s appointment. It wasn’t the physicality of moving Mimi to the appointment—physically she was fit—it was the fact that Mimi had spent her life avoiding doctors at all costs. “You want to have something wrong with you?” She mused, “Go see a doctor! You’ll go in without a worry in the world and come out with ten prescriptions!”

Mimi’s prescriptions included Hershey bars, chocolate milkshakes, and jelly donuts.

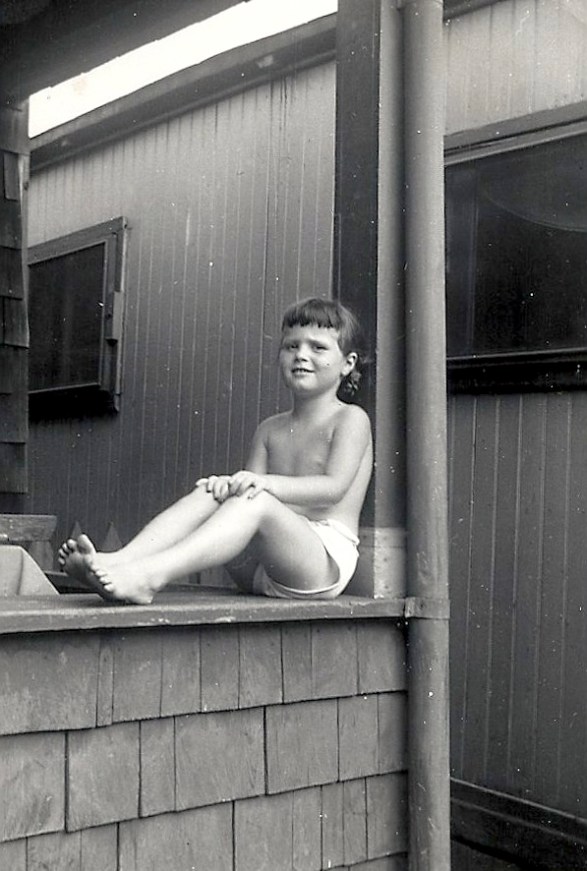

One night, after a particularly taxing day of wrangling Mimi to a doctor’s appointment, I offered to help Mimi get ready for bed. She usually wanted to do it by herself, but that night I saw the fatigue creeping up from her ankles. She was too tired to even wash her face, so after peeling Mimi out of her bra and snuggling her into flannel pajamas, I settled her into the broken-down recliner where she slept, the place that had been my grandfather’s until he vacated that throne. I found a clean facecloth and put warm water and a bit of soap on it. I brought the facecloth to the recliner and Mimi tilted her head up, closed her eyes, and let me wash her face.

I looked down at my grandmother’s feet, toes squeezed together tight inside nylon knee-highs. “Want a foot massage?” She smiled. I squeezed my fingers inside the tight band just under her knees and peeled off the stockings. I fetched a basin of warm water and soaked the towel, then washed and dried Mimi’s feet. She was bashful, but didn’t resist. I cuffed her pajama pants as high as they would go, and rubbed lotion up and down her legs.

“Well, shit,” Mimi joked, “I’d have shaved if I’d known this was going to happen!” I reminded her that she only shaved for weddings and funerals, and Mimi’s quick wit was on-point.

“Well I hope you’re not dressing me for my wake! I’m not dead yet! And I know I’m not getting married…Or am I?” Mimi couldn’t remember the basics of life, but she never missed an opportunity to crack a joke.

I creamed Mimi’s feet, and then found a cozy pair of socks that I put on her before tucking the blanket in tight. I stood to leave, but Mimi held out her hands so I washed, dried, and creamed those too.

“Ok,” I said, “You all set?” I should’ve known better, I should’ve known my Mimi.

“Do we have any cookies?” Mimi asked, “And maybe a little glass of milk?” I set a tall stack of Oreos and a short glass of milk on her side table that was cluttered with expired coupons and crystal dishes full of half-disintegrated rubber bands and paper clips distorted beyond utility. I kissed Mimi goodnight, and was walking away when she grabbed my hand.

“Nanny must’ve sent you from heaven to take care of me,” Mimi said, and I choked back tears because I felt it too, knew she was right. The strength I had was coming from somewhere outside me, but there was nowhere else I wanted to be. “I don’t know what I’d do without you,” Mimi said, “Please don’t ever leave me.”

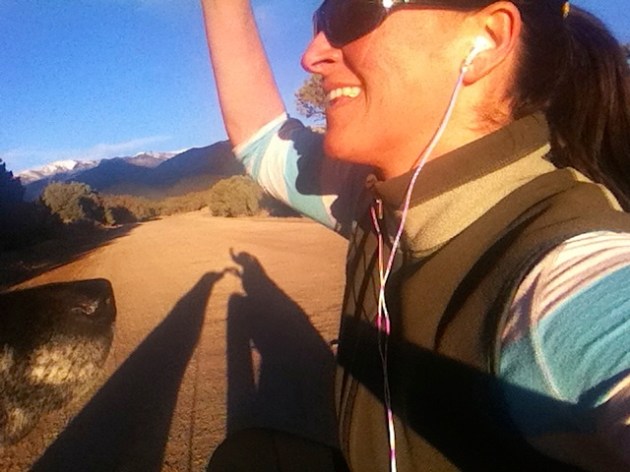

I’m not afraid to do the silly thing.